![John Martin's early 19th-c. vision of the beach at Stabiae]()

John Martin’s early 19th-c. vision of the beach at Stabiae (detail)

6.16.17-22: The Smell of Sulfur

This post belongs to a serialized translation and commentary of Pliny the Younger’s letters (6.16 and 6.20) to the historian Tacitus about the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. This is the sixth (and last) installment for letter 6.16.

The Elder Pliny, his friends, and their servants have fled the villa of his friend Pomponianus at Stabiae. Rather than risk burial from collapsing roofs, they have decided to take their chances along the shoreline while pumice continues to rain down. It is probably between 5:30-6:30 a.m. (see also Sigurdsson’s eruption timeline here); sunrise at Stabiae (Lat. 40.696518 N; Long. 14.483070 E) on 25 August was at 5:28 (NOAA solar calculator; see Part 4 for instructions on how to use it).

17 Iam dies alibi, illic nox omnibus noctibus nigrior densiorque; quam tamen faces multae variaque lumina solvebant. Placuit egredi in litus, et ex proximo adspicere, ecquid iam mare admitteret; quod adhuc vastum et adversum permanebat.

17 It was now daylight elsewhere, but over there was a night blacker and thicker than all other nights; which, however, numerous torches and diverse lights were cutting through. It pleased (them) to go down to the shore, and see close-up whether the sea would now permit access; but still the waves continued to be heavy and contrary.

It is now a new day. The chiasmus of dies alibi, illic nox does two things. First, it briefly withdraws the reader from the scene to understand that this disaster was local, not global (though to many at the time, it seemed global; see epistula 6.20). It is but a brief breath before we plunge back into the story. Second, Younger Pliny uses the calendrical change to heighten the contrast between a ‘normal’ day and this extraordinary one, in which the sun has risen (the root of dies has the same Sanskrit root as Greek διός, meaning ‘light of heaven’ ['god' = Greek Ζεύς, Latin deus]), but night hangs on at Stabiae (illic). In fact, it is a darkness more impenetrable than any night known (comparative adjective with ablative of comparison omnibus noctibus). In the first clause, note the repetition of dark words that emphasizes the blackness: nox…noctibus nigrior densior. The main verb erat is gapped (which is common).

The relative pronoun quam carries night (nox) over to the other half of the sentence, where there is a small manuscript problem. While I retain Mynors’ preference (solvebant, deriving from θ [t], Codex Taurinensis D.ii.24), the better M and γ manuscripts read solebantur (which doesn’t make sense), emended to solabantur (“were lightening/mitigating”) by Gottlieb Cortius in his 1734 edition; ref. Church and Brodribb, Select Letters of Pliny the Younger, new ed. (1881) 171-2. The adverb tamen serves as a hinge point; by either reading, torches (faces) and other sources such as lamps and lanterns (lumina) were fighting the darkness — loosening or lessening it.

Standing back, one can see the darkness contained and contested; globally by daylight at the start of the sentence, and locally by the man-made technology at the end. The words multae and varia stress how many individuals are fleeing with whatever illumination they have to make their way: points of light against the gloom.

Lumina survive from the eruption; most elaborate is the bronze lantern from Oplontis (right). As the British Museum exhibition notes: “The lanterns they carried were fuelled by olive oil stored in the cylindrical reservoir at the base, and originally had shades made of thin sheets of animal horn” (parchment shades were also possible). Small holes in the lantern hood would have allowed smoke to exit and provided oxygen to the flame. See Pompeii in Pictures II.4.8 for a location where two such bronze lanterns were recovered along the Via dell’Abbondanza. There is a definitive study of bronze lamps from Pompeii and Herculaneum, though most lamps were made of terracotta.

The company decides to make their way to the shore in hopes that they can launch a boat. Again, we do not know where Pomponianus’ villa was along the shore, or with respect to the shore. The principal Roman structures discovered and first excavated by the Bourbons at Stabiae are on the Varano plateau, a bluff with a steep (ca. 45°) slope leading down to the present shoreline, but Roman remains are also present elsewhere on that coast.

![Close-up of Stabiae area from the northwest]()

Stabiae area from the NW, showing Varano plateau and approximate ancient shoreline. Map imagery from Google Earth. Shoreline estimate from M. Mastroroberto and G. Bonifacio, “Ricerche archeologiche nell’ager stabinus,” in Bonifacio and Sodo, Stabiae (cited below), 154, fig. 1. Click on image to enlarge.

The villas perched on that bluff were multi-level in nature; the Villa Arianna, for instance, had an access ramp that began at about 15 m. above sea-level, switching back up the slope past vaulted substructures built to hold back subsidence of the soil, and terraces that accessed a grotto, fountains and other features, now mostly eroded away. The ground floor of the main living area of the villa, on top of the plateau, rests at 55.6 m. above sea level, such that the complex traverses more than 40 m. of elevation. Even at that height above waterline, however, sufficient volcanic debris rained down to collapse roofs and bury the villas (leaving ca. two meters of deposits).

![]()

Map of initial white pumice fall (white line) and subsequent grey pumice fall (red line), from L. Gurioli et al., Geology 33.6 (2005) 441.

[For details and plans of the Villa Arianna, see A. De Simone, "Villa Arianna: configurazione delle strutture della Basis Villae," in G. Bonifacio and A.M. Sodo, eds., Stabiae: Storia e Architettura, Studi della Soprintendenza Archaeologia di Pompei 7 (2002), 41-52, esp. figs. 3-4).]

![Looking towards the shoreline of the Bay of Naples; map imagery form Google Earth.]()

Looking towards the shoreline of the Bay of Naples; map imagery from Google Earth. Herculaneum, Pompeii, and Stabiae were all closer to the sea in antiquity. Click on image to enlarge.

In Pliny’s day, the shoreline was some 400 m. closer to the base of the Varano plateau than it is today. But there’s no way to know how far a walk it was for Pliny from the villa to the shore, or whether heading up the mountain ridge to the south would have been an option. Stabiae was at the edge of the last major “pyroclastic density current“ of the eruption (see below, section 18), so although he couldn’t know it, the Elder Pliny was not far from safety.

Placuit egredi is a nice example of an impersonal verb with infinitives (egredi [deponent] and adspicere), the dative of the persons ‘pleased’ being omitted. Egredior is often used in contexts of ‘setting sail’ or ‘disembarking from a ship’, so it’s particularly appropriate. They must get close enough (ex proximo) to see if wind and wave allow excape. Autopsy (adspicere) introduces an indirect question: whether at this point (iam) the sea will suffer their passage. Earlier, Pomponianus had tried to leave that way but had been prevented, and with quod as a relative pronoun referring back to mare, Pliny tells us with the ongoing past action of the imperfect tense (permanebat) that impossibly high and heavy water continues to be against them. Permaneo in this context spells doom; it implies conditions will ‘stay that way until the end’. The end is, indeed, near.

18 Ibi super abiectum linteum recubans semel atque iterum frigidam aquam poposcit hausitque. Deinde flammae flammarumque praenuntius odor sulpuris alios in fugam vertunt, excitant illum.

18 There, lying down upon a cloth cast aside, once and then again he asked for cold water and drank it. Then fire and the smell of sulphur — the harbinger of flames — turned the others to flight, and roused him.

Pliny can go no further. At the ships, he lies back, on a sheet of cloth that has been tossed aside (abiectum, ms. M) or placed down (adiectum, ms. γ). Most translators translate linteum as sailcloth, which seems reasonable, given the context. The wind has been against them, and they’d need to row to get offshore. However, tossing aside a sail, rather than furling it, seems needless. The same word has just been used in section 16, referring to linens large enough to bind cushions to the refugees’ heads; these are at hand and could have served the purpose. It is not an important distinction; either interpretation provides just a bit of dignity and comfort for Pliny’s last moments upon the pumice stones.

Elder Pliny has two slaves with him (section 19), whom he asks more than once for cold water to drink. Cold water features prominently in the De Medicina by the encyclopaedist Aulus Cornelius Celsus, written in the Julio-Claudian period. Cold water is advisable for digestion (I.2.2, 2.10; I.8.3-4), but not for exertion (I.3.6-7, 3.23), even though it does bring the temperature down (I.3.12, 3.27). Elder Pliny himself discusses cold, clean water in the Historia Naturalis XXXI.31-41), in which he includes this line (XXXI.37):

aquam salubrem aeris quam simillimam esse oportet.

Healthy water ought be most like air.

Amidst the heat and debris, a cold drink seems a good idea, but what will kill Pliny is a lack of air.

![]()

Pyroclastic density current (PDC), Eruption of Mt. Pinatubo, The Phillipines, 15 June 1991. Photo: Alberto Garcia/Corbis

The smell of sulfur. The sign and sight of fire. Rolling toward the party on the beach (they seem to be waiting for Pliny to feel better) is the sixth and final major eruptive column collapse of the Vesuvian eruption. The flow of that column collapse left about one meter of debris at Stabiae, near the limit of its power. But its approach must have been terrifying. Only in the last 30-40 years of volcanic research has this phenomenon really begun to be documented and understood.

First dubbed a “nuée ardente,” or “burning cloud” after the eruption of Mt. Pelée on the island of Martinique in 1902 which destroyed the town of St. Pierre and killed about 30,000 people, the phenomenon of a volcanic avalanche is now known as a “pyroclastic density current” or “PDC” by volcanologists. Terms such as pyrolastic flow (for higher density components of the current that hug the ground) and pyroclastic surge (for lower density components not inhibited by topography) are still commonly used, however. The PDC is a mix of solid fragments ejected from the volcano and hot gases that, mixed together, behaves as a fluid, and travels with great power at high speeds. The speed of the fourth major PDC, the first to hit Pompeii, has been estimated at 50-60 meters/second, and its temperature has how been estimated at about 300° Celsius (see also L. Gurioli et al, Geology 33.6 [2005] 443).

A descriptive illustration of the force and effect of the first pyroclastic density current (which destroyed Herculaneum) was created by the BBC for their 2003 documentary, Pompeii: The Last Day:

.

![]()

Isopach map of PDC depth from the AD 79 Vesuvian eruption (bottom map; the top map shows the 2nd-millennium B.C. Avellino eruption); click to access a PDF of L. Gurioli et al.’s article.

The depth of the sixth, and last major, PDC, which reached Stabiae, was about one meter, tapering off quickly up the slopes to the south. Weary though he was, the sight and smell of this fiery avalanche was enough to rouse Elder Pliny one last time.

19 Innitens servolis duobus adsurrexit et statim concidit, ut ego colligo, crassiore caligine spiritu obstructo, clausoque stomacho qui illi natura invalidus et angustus et frequenter aestuans erat.

19 Leaning upon two slaves he stood up and then immediately collapsed, as I gather, because his breath was constricted by the particularly dense murk and his windpipe was closed up, which for him by nature was weak and narrow, and often inflamed.

The pyroclastic density current heading towards the beach at Stabiae had prompted everyone else to run for their lives. But two slaves stood with Elder Pliny to help him up. Whether that effort had been too much for him in an atmosphere thickening with dust and noxious fumes, or whether it was because it was at that moment the rolling cloud hit them, is unknown. No more mention is made of the slaves, and whether they survived. As human props, they were not important to Pliny’s letter. However, it seems likely that they might have made it, both as witnesses to the Elder’s last moments (Pliny has to say “ut ego colligo” in order to explain how his uncle died, because he wasn’t there), and because the PDC by now may have dimmed to the point that it was not immediately deadly for robust persons.

Bob Thompson from the University of Durham, who has worked at Montserrat, has put together a useful page that explains how volcanic eruptions harm humans. Exposure time to the surge was probably 2-5 minutes; 200° C air (perhaps a high estimate for conditions at Stabiae) can be survived for that long if the air is dry and still. Dust and fumes are more problematic, however. 100-micron and smaller particles go directly into the lungs. Flying dust and fumes also reduce the oxygen concentration.

![]() Commenters have often noticed a problem with the word ‘stomachus,’ which technically means the “gullet,” or “esophagus.” As the inlet for food, it has an extended meaning of “stomach,” and also “taste” or “good digestion.” In that respect, the word is inaccurate, since the gullet does not have to do with breathing — the windpipe (trachea) does. Regardless of the anatomical distinction, Pliny’s throat was choked up, and he perished from asphyxiation. (Dr. Jacob Bigelow, in an 1856 communication to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, disagreed, but he was unaware of pyroclastic density currents!) Pliny specifically mentions the density of the cloud (crassiore caligine) as the reason his breath was obstructed (starting a nice string of six ablatives with an instrumental ablative followed by two ablative absolutes). Stomacho serves as the antecedent to the relative clause begun by qui which then explains that Pliny had a ‘pre-existing condition,’ which we might have suspected from his earlier characterization as a heavy snorer. Such a condition may have included asthma, as Retief and Cilliers (Acta Theologica 26.2 [2006] 107-14) and others have hypothesized. Specifically, his windpipe was weak, narrow, and often swollen. It is no surprise or mystery, therefore, that Pliny perished, running out of oxygen in attempting to lift his ample frame and flee with the rest of his friends while the surge hit. That he was not carried away by his friends or slaves can be explained by their own need for self-preservation.

Commenters have often noticed a problem with the word ‘stomachus,’ which technically means the “gullet,” or “esophagus.” As the inlet for food, it has an extended meaning of “stomach,” and also “taste” or “good digestion.” In that respect, the word is inaccurate, since the gullet does not have to do with breathing — the windpipe (trachea) does. Regardless of the anatomical distinction, Pliny’s throat was choked up, and he perished from asphyxiation. (Dr. Jacob Bigelow, in an 1856 communication to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, disagreed, but he was unaware of pyroclastic density currents!) Pliny specifically mentions the density of the cloud (crassiore caligine) as the reason his breath was obstructed (starting a nice string of six ablatives with an instrumental ablative followed by two ablative absolutes). Stomacho serves as the antecedent to the relative clause begun by qui which then explains that Pliny had a ‘pre-existing condition,’ which we might have suspected from his earlier characterization as a heavy snorer. Such a condition may have included asthma, as Retief and Cilliers (Acta Theologica 26.2 [2006] 107-14) and others have hypothesized. Specifically, his windpipe was weak, narrow, and often swollen. It is no surprise or mystery, therefore, that Pliny perished, running out of oxygen in attempting to lift his ample frame and flee with the rest of his friends while the surge hit. That he was not carried away by his friends or slaves can be explained by their own need for self-preservation.

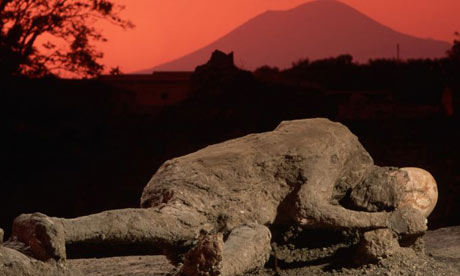

20 Ubi dies redditus (is ab eo quem novissime viderat tertius), corpus inventum integrum inlaesum opertumque ut fuerat indutus: habitus corporis quiescenti quam defuncto similior.

20 When daylight returned (the third from that which he [Elder Pliny] had most recently seen), his body was found whole, uninjured, and clothed as he had dressed: the posture of his body was more like one sleeping than dead.

As noted in Part 4, the Romans counted calendrical dates inclusively, so the third day on which a real dawn appeared was 26 August. Survivors went back to find him the day after he died. An ‘est‘ is gapped after inventum; that gap allows for a stately parade of participles and adjectives following and agreeing with corpus. That the Elder’s body was clothed as he had dressed — and was whole and uninjured — tells us that he was at the edge of the pyroclastic density current, and claims that he was not killed by one of his slaves, as one suspicion circulated in antiquity.

A surviving fragment of a work generally attributed to the Roman historian Suetonius, the Vita Plinii Secundii, itself part of a collection of lives of “Illustrious Men” (De Viris Illustribus, mostly writers), has the following to say about the Elder’s death:

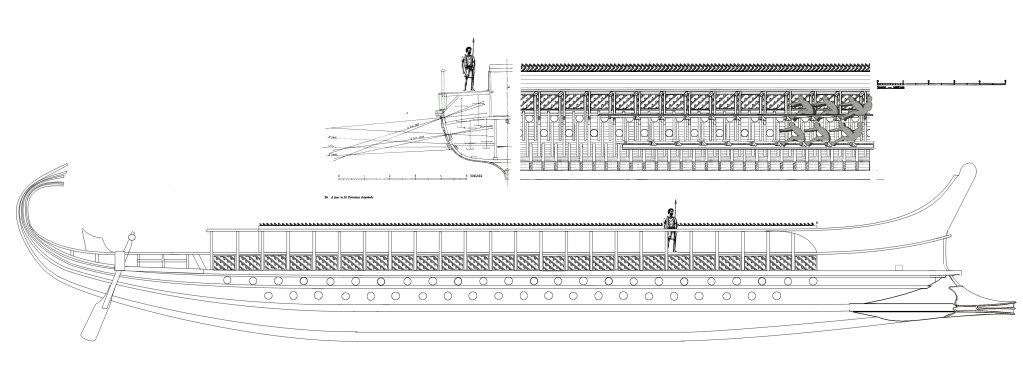

Periit clade Campaniae; cum enim Misenensi classi praeesset et flagrante Vesubio ad explorandas propius causas liburnica pertendisset, nec adversantibus ventis remeare posset, vi pulveris ac favillae oppressus est, vel ut quidam existimant a servo suo occisus, quem aestu deficiens ut necem sibi maturaret oraverat.

“He died in the disaster in Campania; for while he was in command of the fleet at Misenum and while Vesuvius was blazing, he had set out in a Liburnian galley in order to explore the causes (of the eruption) nearer at hand, nor was he able to come back due to adverse winds; he was smothered by the force of dust and cinders, or as some think, was killed by his slave, whom he (Pliny), failing from the billowing heat, had begged to hasten his death.”

Suetonius was a younger contemporary of Pliny and of Tacitus; his lives of Famous Men is thought to the earliest of his works, written perhaps between AD 106-107, not long before Pliny penned the Vesuvian letters. The Younger Pliny helped Suetonius in his political and literary career. Some significant discussion of the discrepancy in death stories between Suetonius’ and Pliny’s versions has occurred, summarized most recently (with helpful bibliography) in a paper by Ryan Sellers. Sellers’ paper is worth a read, as he re-calibrates the ancient perception of an assisted suicide by the Elder Pliny not as a shameful act, but as a noble act of self-determination (in this Sellers is surely correct).

It should be noted, however, that Suetonius is not claiming that the suicide story was the true one; he simply offers that version as an alternate, “ut quidem existimant” (as some people suppose), reporting popular gossip. It does seem likely, however, that Younger Pliny added the detail about a corpus…inlaesum either as a corrective to Suetonius’ published alternative, or as a response to a generally-circulating suicide story about his uncle, so that his addressee, Tacitus, would ‘get it right’ (or ‘get it the way Pliny wanted’). “Inlaesum” is opposite to laesum, from laedo, indicating an acute harm, usually inflicted by another person, in the sense of “doing injury to someone.” Such injury can be physical, but it may also be emotional or reputational. Younger Pliny, for reasons we may not fully fathom, is insisting that his uncle’s body was ‘untouched’.

Younger Pliny follows with a statement that the habitus (posture, position, attitude) of the body was more like a sleeper than a dead man. This of course resonated with visitors to Pompeii after Guiseppe Fiorelli perfected the method of pouring plaster into cavities to re-create the lost organic forms of the city. While we know now that the posture of the bodies at Pompeii resulted from their being almost instantaneously overheated, the impression of sleeping ancients, disinterred from their catastrophic tomb, has proved emotionally powerful to subsequent authors and artists, such as Gormley and McCollum (below).

![]()

Antony Gormley, “Untitled,” 2002, shown at The Last Days of Pompeii: Decadence, Apocalypse, Resurrection exhibition, J. Paul Getty Museum, 2012-13

![]()

Allan McCollum, “The Dog from Pompeii,” 1991, shown at The Last Days of Pompeii: Decadence, Apocalypse, Resurrection exhibition, J. Paul Getty Museum, 2012-13

One might even stretch towards Samuel Beckett’s Imagination Dead Imagine, “to see if they still lie still in the stress of that storm, or of a worse storm, or in the black dark for good, or the great whiteness unchanging, and if not what they are doing.”

![]()

Anne Madden, Traces of Pompeii, 1984-85

![]()

Michael Huey, The Bed (2008), featured in The Last Days of Pompeii: Decadence, Apocalypse, Resurrection exhibition, Cleveland Museum of Art, 2013, from http://iheartphotograph.blogspot.it. As the exhibition catalogue states, Huey repurposes this found photograph to portray Pliny and his mother at home while the mountain erupts outside.

21 Interim Miseni ego et mater—sed nihil ad historiam, nec tu aliud quam de exitu eius scire voluisti. Finem ergo faciam.

21 Meanwhile at Miseum I and my mother — but this has naught to do with history, nor did you want to know anything except about his [Elder Pliny's] death. So I shall make an end.

This interrupted sentence, and the larger issue of how interested Younger Pliny actually was actually in writing history, has recently been treated by A. Augoustakis, The Classical Journal 100.3 (2005) 265-73 and R. Ash, Arethusa 36 (2003) 211-25. Both agree that the interruption piques the curiosity of the reader (today for us, and for Tacitus in the past), prompting the request for a second letter to relate the experiences of Pliny and his mother (epistula 6.20). By specifying (and therefore limiting) Tacitus’ original inquiry (nec tu aliud quam de exitu eius scire voluisti), Pliny can hint that there is more to the story while not seeming too eager to relate it before it has been requested. Despite this false modesty, by which Pliny pretends to step back from history-writing himself, he is certainly interested in facilitating the writing of history. He certainly wanted to state, for the record, the cause of his uncle’s death (sections 19-20, above).

Pliny then states that he will close. That, too, turns out to be a false ending. There’s just one more thing.

![]()

Pliny and Tacitus definitely met each other (and other writers). But the bit about ‘dialogue’ and ‘handful’ is right.

22 Unum adiciam, omnia me quibus interfueram quaeque statim, cum maxime vera memorantur, audieram, persecutum. Tu potissima excerpes; aliud est enim epistulam aliud historiam, aliud amico aliud omnibus scribere. Vale.

22 One thing I shall add: that I have related all the things at which I was present, and those things that I heard right away, when true things are best remembered. You will select the most important bits; for it is one thing to write a letter and another to write a history; one thing to write to a friend, and another to write to everyone. Farewell.

After the ‘saying’ verb of adiciam, we enter indirect discourse, with the accusative me as the subject of the infinitive persecutum [esse], which then governs omnia as the direct object. In this construction, Pliny places all the events (omnia) he has shared next to himself (me) because, as he carefully explains, he was either there himself (the relative clause quibus interfueram), or he heard the information as soon as possible afterwards, when its sources were likely to be reliable (quaeque statim, cum maxime vera memorantur, audieram).

After assuring Tacitus (and all other eventual readers) of the care he has taken with the sources for his account, he then passes off responsibility for the information to his correspondent: tu potissima excerpes (“you, Tacitus, will pick out the most important parts”). This seems to absolve Pliny of the responsibility of editing, but of course his letters were carefully edited before publication.

Pliny’s editing is evidenced in the double synchesis (aliud…epistulam aliud…historiam, aliud amico aliud omnibus) of his highly polished final sentence, capped by a word precious to both Tacitus and both Plinys: scribere. The Younger can claim that a letter to a friend is quite another thing from a historical account written for everyone (everyone literate, at least), but when such a letter is written to a historian, and the letter itself is prepped for general consumption, we can share a shrug of the shoulders and a knowing grin, and look forward to the sequel.

So ends the epistle. As Pliny suspected, it did not satisfy Tacitus’ curiosity, because the historian requested a sequel. In the next post, we will begin translating letter 6.20, which tells the story of how, on the opposite side of the Bay of Naples from where the Elder fell, Pliny the Younger and his mother faced, and fled, Vesuvius’ fury.

Back to Part 7

Forward to Part 9 (forthcoming)

![]()

![]()

Pliny and the Eruption of Vesuvius (Routledge, March 2022) is in press.

Pliny and the Eruption of Vesuvius (Routledge, March 2022) is in press.